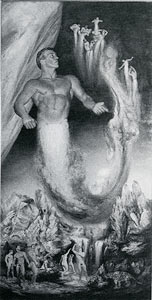

We Inhabit the Corrosive Littoral of Habit, 1940, oil on canvas. Renee Free, JAMES GLEESON, images from the shadows. NGV.

We Inhabit the Corrosive Littoral of Habit, 1940, oil on canvas. Renee Free, JAMES GLEESON, images from the shadows. NGV.

Christopher Allen author of Gleeson's obituary in The Australian writes:

"One of Gleeson's first significant works as a surrealist is indeed set on a beach: We inhabit the corrosive littoral of habit (1940), in which a man's features and a woman's naked torso dissolve, revealing the hollowness inside. The idea remains something of a literary conceit, almost obviously an illustration of T.S. Eliot's poem The Hollow Men (1925)."

Mention of the debt to Dalí is omitted.

|

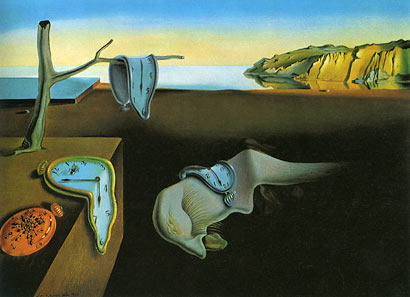

The Persistence of Memory, Salvador Dalí, 1931. MoMa.

The Persistence of Memory, Salvador Dalí, 1931. MoMa.

The painting by Gleeson (left) is obviously a version of Dalí's painting (above). Paintings such as this elicited criticism of his works such as: "James Gleeson worked closest to the accepted idea of surrealism - that is to say, he imitated Dali so closely that he became a pasticheur." Robert Hughes, p. 142, The Art of Australia.

|

Hughes wrote that Gleeson was "fundamentally, a painter of allegories and literary symbols" and that "irrational processes were not of prime importance to him; once you had the symbolic code, the painting could be deciphered at once." p. 144, The Art of Australia; and that Gleeson "only went through the motions" of surrealism's irrational processes (p. 412).

This criticism by Hughes is based on an explanation Gleeson proffered in 1945 for two of his works:

| "In The Citadel I have substituted for war torn brick and stone a symbolic pattern of human flesh, bone , teeth, hair. In Landscape with Funeral Procession I have tried to catch the moment when physical life rejoins the earth, again represented by human flesh. These are the horrors of the concentration camp and the battlefield, seen through the eyes of a surrealist." (Gleeson quoted p. 144, Hughes). |

What Gleeson wrote on his works in 1945 was not outside the ambit of what surrealism is - one only has to think of Ernst's Europe after the Rain and The Eye of Silence, and even Dalí's explanation for his painting Soft Construction with Boiled Beans: A Premonition of Civil War. Hughes' understanding of surrealism though was obviously limited to an imprecise, partial and selective knowledge of Dalí, and points to his distaste for surrealism, more so than anything else. Hughes first condemns Gleeson for being a "pasticheur" of Dalí, and then condemns him for his divergence from Dalí when he can no longer criticise him for producing pastiches!

The interest in the quoting of Hughes here however lies in Gleeson's reaction to such criticism. Rather than defend his work, he merely acquiesced to the criticism. He eventually came to claim his paintings to be the product of purely random processes, in keeping with surrealism as it was understood by critics such as Hughes, when in fact his works were never anything of the sort. He was, it came to be claimed, "fascinated by the world of the unconscious mind revealed by Freud and Jung.", so that paintings of his with homoerotic overtones were given Jungian interpretations (as is claimed in Renee Free's biography on Gleeson).

|

Clouds of Witness, left, is representative of the works Gleeson produced in the 1960s in which his homoerotic fantasies are cloaked by descriptions of these works as being surreal. Paintings such as these which belong in the realm of fantasy kitsch, are ascribed whacky "Jungian" meaning by hagiographers pushing their own barrow like Renee Free. These works did much to discredit art of the imagination in Australia.

(A short note: In 19th century Germany, Plotinus, his Enneads, and like-minded philosophers were very much in favour. The Germans invented the misleading term "neoplatonism" to describe these philosophers. Both Freud and Jung filched Plotinus' ideas on the soul and its divisions, along with the Platonic basis for Plotinus, that an abstraction, IDEA (usually mistranslated as "form" in English), precedes the actual. This IDEA is the "archetype" or "primary form" ascribed to ideas by Jung. The concern of Plotinus was the soul, ψυχή, psyche, hence "psychology" - logic of the soul. A more complete debunking of Freud and Jung lies outside the scope of this essay.

Amazon links: Plotinus' Enneads "Neoplatonism")

Clouds of Witness, 1966, oil n canvas, left panel of commissioned triptych. Fig. 23, Renee Free, JAMES GLEESON, images from the shadows.

|

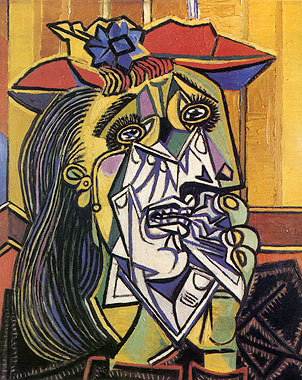

That the criticism of Gleeson by Hughes was motivated by dishonesty is evident by his overlooking other influences on Gleeson; Dalí was never his sole model. Picasso was one obvious early influence. Gleeson's interest in Picasso as a surrealist is not an unreasonable one, after-all, Picasso was the artist Breton originally claimed to represent visual surrealism (surrealism began as a literary movement), and for a short while he formed associations with the surrealists, even producing a cover for the surrealist magazine Minotaur.

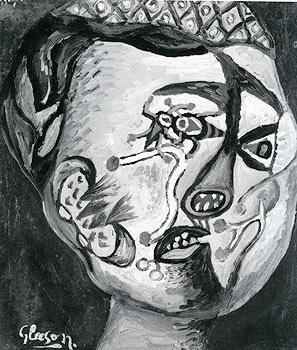

Weeping Head, Gleeson, 1939. Fig. 5, Renee Free, JAMES GLEESON, images from the shadows. NGV.

Weeping Head, Gleeson, 1939. Fig. 5, Renee Free, JAMES GLEESON, images from the shadows. NGV.

Gleeson's comments on this painting are indicative of his intellectual timidity:

"I had always had a horror of violence and war. I've tried to put into it the idea of conflict, the eyes like beetles - scorpions attacking each other. The tears are like bent wire - hard; The ear pierced by arrows - the sound of explosions..." p. 18, Free.

Gleeson introduces his own symbology into his Picasso-derived head. It is this disposition to symbology that Hughes criticises. Gleeson's self-stated aversion to conflict means that Hughes' comments are never (publicly) repudiated.

|

Weeping Woman, Picasso, 1937, NGV,

Weeping Woman, Picasso, 1937, NGV,

(Illus. p. 344, Pablo Picasso, MoMa, publisher (with wrong attribution.)

|

One of the curiosities about Gleeson's paintings is that he prefers to keep the sources of his ideas secret. In the book by Klepac, Gleeson cites artists such as Turner and Matta (p.16) as influences, on his style and subject thus establishing an orthodox pedigree for his images. This ascription is a fabrication. Perhaps this was to deny critics like Hughes ammunition? Alternately though, by keeping those who exerted influence on him a secret, Gleeson could lay claim to an originality without precedent. Gleeson did, as Hughes states, begin as a pasticheur of Dalí, but Dalí was not the sole artist whose ideas appear in his work without any attribution. Gleeson has plundered comic books, Picasso, Johfra and Giger. Of those only Picasso is considered "orthodox", hence the absence of reference to the others. Eventually his art diverged from these sources - producing paintings of the Australian landscape "surrealised". But this surrealised landscape which at first appeared 'without precedent' is obviously dependant upon a merger of Picasso and Giger first, before absorbing the oeuvre of others, like Johfra's, into his own visual repertoire.

Gleeson's own statements on his works are intended to give his art an impeccable pedigree. In Klepac's book he claims:

| "I've always been fascinated by Turner because of his mastery of atmosphere through colour. Among the living artists, I find Matta a constant source of interest...because of his extraordinary skill in using perspective to float enormously complex structures in space." (Gleeson quoted p. 17, Klepac). |

Ulysses Deriding Polyphemus - Homer's Odyssey, William Turner (Joseph Mallord William Turner), oil on canvas, 1829. Pl. 27, William Gaunt, Turner. National Gallery London.

Ulysses Deriding Polyphemus - Homer's Odyssey, William Turner (Joseph Mallord William Turner), oil on canvas, 1829. Pl. 27, William Gaunt, Turner. National Gallery London.

Gleeson claims an impeccable pedigree as the inspiration for his artistic output. Science-fiction elements in his oeuvre which might be caustic to this carefully cultivated pedigree have to be excised.

|

A Grave Situation, Matta (Roberto Antonio Sebastián Matta Echaurren), oil on canvas, 1946. Illus. 209, Sidra Stich (editor), ANXIOUS VISIONS, surrealist art. (Promised to) Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago.

A Grave Situation, Matta (Roberto Antonio Sebastián Matta Echaurren), oil on canvas, 1946. Illus. 209, Sidra Stich (editor), ANXIOUS VISIONS, surrealist art. (Promised to) Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago.

Gleeson's claim to being influenced by Matta may have some merit, but only for one of his works. He makes his claim in Klepac's book when he was still working on his painting Preparations at Patmos, where what looks like Matta's central figure (minus its 'arms') is at the centre of Gleeson's work-in-progress.

|

According to Free

| "Gleeson's lens has been applied to the littoral of [the Australian state of] Queensland between Noosa and Maroochydore. His inner lens has metamorphosed this in large drawings and later paintings done in Sydney... The metamorphic process has developed from embracing individual forms to embracing the cosmos." (p. 34, Free). |

The claim here is that Gleeson's inspiration is derived from the flotsam and jetsam that washes up on the Australian coast, rendered by an artist with an impeccable pedigree. However, the crustacean elements which are fused with the landscape which appear in his works are not, as is claimed, the elements that are found washed up on the Australian littoral, but elements of Giger's crustacean Alien monster fused into the Australian landscape. If anything can be said about Australian art, it is that it is embarrassingly unashamedly nationalistic. The landscape is the cause celebré of Australia's mindless nationalists and is used to define what it is to be "Australian". And though all artists cannot but be influenced by those who preceded them, Gleeson resolutely denies, by his silence, the existence of any influence by artists who might contradict his carefully crafted persona, and instead the source of his inspiration is ascribed to the Australian landscape. (Of course, Dalí made similar claims about the landforms of Cadeques which he claimed to be the inspiration for his surrealist forms.)

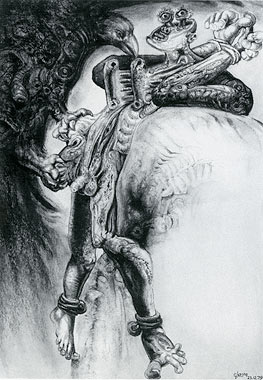

Prometheus i, 1979, charcoal. Fig. 29d. Renee Free, JAMES GLEESON, images from the shadows. Collection of Frank O'Keefe.

Prometheus i, 1979, charcoal. Fig. 29d. Renee Free, JAMES GLEESON, images from the shadows. Collection of Frank O'Keefe.

|

Woman Crying, Picasso, 1937. Illus. p. 345, Pablo Picasso, MoMa, publisher. Musée Picasso, Paris.

Woman Crying, Picasso, 1937. Illus. p. 345, Pablo Picasso, MoMa, publisher. Musée Picasso, Paris.

The elements in the Gleeson drawing (left) are derived from Picasso (above).

|

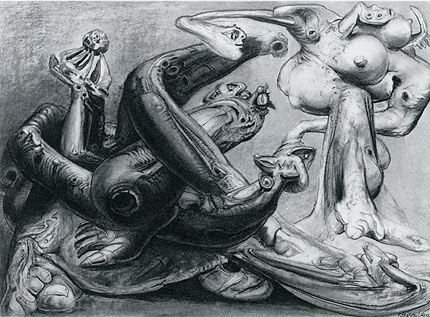

The Judgement of Paris, viii, pastel. Fig. 28f, Renee Free, JAMES GLEESON, images from the shadows. Collection of Frank O'Keefe.

The Judgement of Paris, viii, pastel. Fig. 28f, Renee Free, JAMES GLEESON, images from the shadows. Collection of Frank O'Keefe.

|

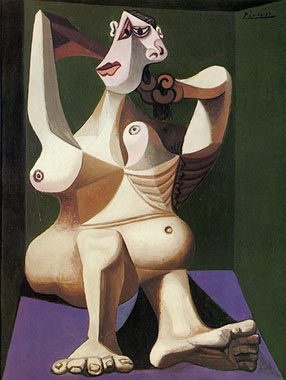

Woman dressing her hair, Picasso, 1940. Illus. p. 366, Pablo Picasso, MoMa, publisher. Private Collection NY.

Woman dressing her hair, Picasso, 1940. Illus. p. 366, Pablo Picasso, MoMa, publisher. Private Collection NY.

|

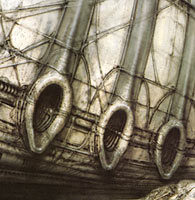

Alien sketch (airbrush), Giger, 1978. Illus. 396, p. 25, GIGER'S ALLIEN, film design 20th century fox, Morpheus International (publisher).

Alien sketch (airbrush), Giger, 1978. Illus. 396, p. 25, GIGER'S ALLIEN, film design 20th century fox, Morpheus International (publisher).

|

Alien wreck, model for film alien, Illus. 397 D, p. 26, GIGER'S ALLIEN, film design 20th century fox, Morpheus International (publisher).

Alien wreck, model for film alien, Illus. 397 D, p. 26, GIGER'S ALLIEN, film design 20th century fox, Morpheus International (publisher).

|

Alien sketch (airbrush), Giger, 1978. Illus. 375 A, p. 29, GIGER'S ALLIEN, film design 20th century fox, Morpheus International (publisher).

Alien sketch (airbrush), Giger, 1978. Illus. 375 A, p. 29, GIGER'S ALLIEN, film design 20th century fox, Morpheus International (publisher).

|

The elements that go to make up the Gleeson drawing (top left) are derived from Picasso (top right), and from Giger's Alien wreckage (middle left, middle right, bottom left). Gleeson has incorporated not only the alien-wreck design, but also Giger's stylised vaginas (detail below). Though obviously indebted to Giger, Gleeson's silence can be explained thus: the arts orthodoxy in Australia considers Giger to be a "science-fiction" illustrator - not artist - and this would negatively affect Gleeson's artistic bona fides.

Giger detail

Giger detail

|

Gleeson detail

Gleeson detail

|

|

The Judgement of Paris, iv, pastel. Fig. 28d, Renee Free, JAMES GLEESON, images from the shadows. Collection of Frank O'Keefe.

The Judgement of Paris, iv, pastel. Fig. 28d, Renee Free, JAMES GLEESON, images from the shadows. Collection of Frank O'Keefe.

|

Carnaval der ijdelheid [641], Johfra Bosschart, 1959. Oil on panel.

Carnaval der ijdelheid [641], Johfra Bosschart, 1959. Oil on panel.

Illus. p. 148, JOHFRA, Hoogste lichten en diepste schaduwen (Johfra, brightest light and deepest shadows). ISBN 9021589044

|

Lemurisch heimwee [429], Johfra Bosschart, 1961. Oil on ?.

Lemurisch heimwee [429], Johfra Bosschart, 1961. Oil on ?.

Illus. p. 168, JOHFRA, Hoogste lichten en diepste schaduwen (Johfra, brightest light and deepest shadows). ISBN 9021589044

|

The elements that go to make up the Gleeson drawing (top left) are derived from Dutch artist Johfra (top right & top left). Gleeson merely changed the fantastic landscape of Johfra into one more recognisably Australian.

Though wildly original, there is an element of kitsch in many of Johfra's works.

(a Johfra website - with very heavy java - can be accessed here)

Gleeson did however reintroduce the anatomical elements of his early painting The Citadel.

|

The Keeper of Used Shadows, James Gleeson, 1986, oil on canvas. Pl. 8, Lou Klepac, JAMES GLEESON, landscape out of nature.

The Keeper of Used Shadows, James Gleeson, 1986, oil on canvas. Pl. 8, Lou Klepac, JAMES GLEESON, landscape out of nature.

|

|

|

|

Above & Left, Sorcerer-guides to SHADOWLAND: "Sheelba of the eyeless face", and "Ningauble of the seven eyes". "Fafhrd the Barbarian and the gray mouser". Drawing by Howard Chaykin. Pp. 38-39, Planet Comics, "World's Finest Comic Monthly", no. 110, c. 1973(?)

Wiki link to "World's Finest Comics"

The elements that go to make up the Gleeson painting (top left) are derived from a comic book. In the comic book the figures are sorcerers who provide the heroes directions to "shadowland"; the figure in Gleeson's painting is the keeper of used shadows. Either Gleeson filched this idea, or we are here provided with incontrovertible proof of Jung's "archetypes" which float in the ether.

By keeping the sources of his ideas a secret, coupled with the general ignorance of art of any kind (which includes comic book art), Australian sycophants of Gleeson have been producing hagiographies of a very mediocre artist; albeit one with an exceptional technical skill in painting.

|

Gleeson, in Klepac's book claims:

| "...in the later series [of paintings] which began in 1983 the process is much less subject to rationalization. Most of them spring from drawings made in one session and without any definitely pre-conceived intention. The forms develop out of the quasi-automatic movement of the charcoal more or less random, though no doubt guided by an aesthetic instinct..." (p. 18, Gleeson quoted by Klepac). |

And Klepac goes on to state:

| "Not even Gleeson can be the final interpreter of this amazing series of late works. The artist has acted almost as a 'medium' to these images which have come to him in an avalanche after fifty years..." (p. 9, Klepac). |

Thus we have Free telling us that Gleeson's images are derived from a Jungian ether (wherein which must lie the "Collective Consciosness"), and Klepac telling us that he has the abilities of the medium to tap into this ether... Remarkably, and uncannily, the sources of his ideas which can be traced to works by artists who Gleeson refuses to acknowledge or mention, must have been transmitted by those artists into Jung's ether for our medium, Gleeson, to tap into and retrieve.

Demetrios Vakras 30/10/2008.

|